I Know a Lot, and That is a Problem

The “Curse of Knowledge” can hinder conversation and professional advancement, or make job opportunities go to the best communicator rather than the most skilled or competent individual.

Sometimes we struggle to explain something that we know well. It can be hilarious but also deeply frustrating. It happens because we forget what it is like to not knowing. We have all experienced this curse of knowledge. Let’s see if I can succeed in telling you what it is and how to overcome it!

Once you understand a concept or master a skill, your brain automatically assumes that others have a similar understanding, making it difficult to explain things in a simple or beginner-friendly manner. Classic examples of the curse of knowledge are found in professors, who might inadvertently skip over foundational ideas because they seem obvious to them, forgetting that their students do not yet have the same information. In work or social settings, experts often use jargon or compressed explanations that make perfect sense to them but confuse others.

What is it?

The curse of knowledge is a cognitive bias that occurs when someone, once they learn something, finds it hard to imagine not knowing it, and therefore struggles to communicate clearly with others who don’t share that knowledge (#here). The term was coined by economists Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein and Martin Weber in their 1989 article “The Curse of Knowledge in Economic Settings” (#here). It was meant to conceptualize the idea that once your mind becomes efficient at something, you no longer consciously register the many steps, logical flow, or background assumptions behind your reasoning. Non-obvious connections between data, processes and ideas become second nature to you. Therefore, when trying to explain how something is done, you unconsciously omit a lot of information, generating gaps that a novice would need fill in. Camerer, Loewenstein and Weber argued that our inability to ignore what we already know sustains informational imbalances even when individuals sincerely try to communicate clearly. This creates a subtle but powerful distortion in markets and decision-making because experts and insiders overestimate how much others understand. They highlighted two intriguing consequences of this bias. First, knowledge can backfire. This is because agents that have more information may assume that others share their insight and, as a result, make poor strategic choices. A seller, for example, might overprice a product, believing that buyers will OBVIOUSLY recognize its full value, while an investor might misjudge market reactions because they assume everyone sees what they see. Paradoxically, however, the curse of knowledge can also reduce market inefficiencies. This happens when well-informed actors mistakenly believe others have similar information, making them behave more transparently. Also, in “The curse of knowledge in reasoning about false beliefs”, Susan Birch and Paul Bloom (#here) explain that people who know the outcome of a situation have difficulty reasoning about others’ beliefs, especially false beliefs. In other words, once you know what really happened, you find it hard to imagine how someone would think that it happened differently. This is significant because someone’s knowledge can compromise their ability to reason with another person about an event.

Of course you know that it happens in the brain!

There appears to be some distinct neural systems that help make sense of why the curse of knowledge occurs. The right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ) is implicated in switching from self-perspective to other-perspective (this is, inhibiting one’s own perspective to consider another’s). A study found that human participants, when asked to mimic the actions of others, did poorly when their rTPJ was stimulated (#here). In another study by Nejati and colleagues (#here), rTPJ stimulation altered the discrimination between self and non-self, indicating that this brain region plays a causal role in the distinction of self vs. others. These results were interpreted to mean that when rTPJ-mediated switching becomes inadequate, people fail to contextually suppress their own knowledge when considering what others know. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is strongly associated with self-referential thinking (thinking about oneself). Thinking about our own thoughts and behaviors and those of others are important for self-conscious social species. This is called metacognition. One analysis has found overlapping but separable representation of self vs. others in mPFC (#here). In short, the mPFC biases people toward thinking “I know this” rather than asking “what do they know?” This means that the mPFC makes experts rely too heavily on themselves about how knowledge works, making it harder for them to understand how a novice brain works. Therefore, effective perspective taking requires a dynamic shift between self-knowledge and others’ minds. When metacognition is poor, the ensuing lack of self-awareness can lead people to fall victim to the curse of knowledge.

We are not all the same

The curse of knowledge doesn’t strike everyone equally. Research across psychology, education, and communication shows that its intensity depends on level of expertise, age, cognitive empathy, and context. The most vulnerable appear to be experts and specialists. The reasons are that the more deeply you know a topic, the more automatic and compressed your mental models become. Experts no longer consciously recall the intermediate steps, or mental scaffolding, that they once needed to master something. Consequently, when explaining something, they overestimate others’ background knowledge, and skip key steps. For example a study by Stanford researchers asked people to tap melodies, which went from “Happy Birthday to You” to “The Star-Spangled Banner”. Tappers predicted that about half of the listeners would succeed in recognizing the tune. Yet, the actual success rate was a mere 2.5%. That is, just 3 out of the 120 tunes presented to them. The tappers, who had a tune in their head, just simply could not imagine what it was like not to recognize it (#here). Instructors, professors and domain experts are especially at risk because they consistently overestimate students and trainees understanding of a topic. They often fail to “chunk” knowledge to reduce the burden of access to basic steps, reinforcing the curse of knowledge. Children can fall victim of the curse of knowledge as well, but for different reasons. Birch and Bloom found that even 3- to 5-year-olds were affected by their own knowledge when inferring others’ false beliefs (#here). Moreover, more recent follow-up studies found that removing privileged information improved children’s performance. Sometimes, even the non-expert are situationally vulnerable because the curse can affect anyone having privileged information (secret knowledge). Then they try to explain something immediately after learning it, which feels obvious to them because they do not consider the so-called informational asymmetry. By contrast, people with high cognitive empathy or trained in perspective-taking are less affected. Think clinicians and psychologists who frequently deal with patients. Also, teams addressing with multi-disciplinary problems and that are naturally composed by people with different expertise generally practice iterative feedback to ensure that every member of the team is “on board”.

Why does is (likely) happen?

According to the Theory of Mind, the curse of knowledge may have likely arisen as an evolutionary by-product of the cognitive adaptations that made humans extraordinarily successful at understanding and predicting one another’s behavior. This innate adaptation may have allowed our ancestors to improve success in coordinated hunting by anticipating partners’ moves from partial information. It may also have helped to deceive competitors, or to negotiate alliances between tribes, by transferring knowledge in ways that were sufficiently understood by kin but cryptic to rivals. It is also thought that our brains have evolved to compress information for speed of decision making, increasing survival. Therefore, once a skill is mastered, it becomes automatic, like effectively throwing a spear without any conscious calculation. In other words, our brains have been modeled to conduct many behaviors in autopilot. This very efficiency, however, makes it hard to mentally rewind and reconstruct the steps that a naïve spear-thrower must learn. Evolution, it seems, have favored the fast actor, and not the slow teacher. Moreover, in ancestral groups, being seen as knowledgeable or competent conferred status and mating success. Then, communicating in ways that signaled the difficulty in acquiring a skill, by using complex language, may have been adaptive. Of course, the same can become maladaptive in large societies where success depends on being understood rather than being seen as clever.

Practical takeaways

If you are interested in clearly conveying knowledge or ideas, here are some actionable pointers to overcome the curse of knowledge. Start with empathy mapping. Visualize what your audience knows, feels, and needs before you speak or write. Try this by mapping audience knowledge explicitly: Ask “What do they not know?” rather than “What do they know?” Start with what everyone with zero exposure to the skill, topic or idea, must know. Avoid jargon and shortcuts like the pest. Break down complexity to easy-to-understand chunks. Test your explanations with somebody less familiar with the topic. Use analogies. Familiar examples or metaphors usually provide a platform from which novices can build up. To overcome the curse of knowledge, you may also try to use the SUCCES framework (#here). Start with Simple by strip your message down to its essence. Focus on one core idea that even a beginner can grasp. Try to “explain it to a child”. Studies in science education have shown that experts’ clarity improves significantly when they deliberately adopt this technique. Then make it Unexpected, Surprise your audience to jolt them out of assumptions and make them curious to know more. Keep it Concrete: by using real experiences instead of abstract jargon so others can visualize what you mean. Build Credibility by grounding your points in actual and verifiable evidence. Make it Emotional by appealing to feelings and values of your audience or readership, not just logic. Finally, wrap it all into Stories. That is, narratives that turn abstract concepts into relatable experiences that people will remember. And remember, the goal isn’t to sound smart. It is to make others understand and care.

Why it matters

The paradox is that the same evolutionary forces that made us the most communicative species on earth also built into our mind a blind spot. The curse of knowledge, therefore, isn’t a flaw of intelligence. It is the inescapable shadow of our ability to understand the minds of a social group. This matters enormously in today’s era of rampant misinformation because it distorts how accurate information is shared, received and trusted (#here). When experts assume that others know what they know, they tend to communicate unclearly. This is, by using jargon, skipping context, or oversimplifying matters. This creates a vacuum of understanding that misinformation eagerly fills. People who explain things clearly, regardless of accuracy, often sound more convincing than those who are right but are difficult to follow or offer nuances. As a result, the best communicator can appear more credible than the best expert. Moreover, the curse of knowledge blinds experts from understanding how misinformation spreads. They underestimate how easily others can misinterpret data, overlook context, or fall for emotionally charged narratives that are not based on trustworthy data. This overconfidence can make them dismissive or condescending toward the uninformed, widening the communication gap between the academic community and the general public.

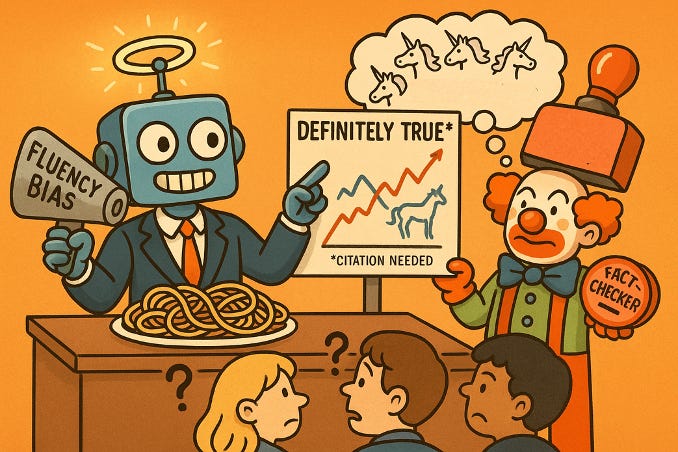

The problem may even be exacerbated by Artificial intelligence. Large language models have become exceptionally good at explaining things clearly, but also are prone to generating false or unverifiable content, called “hallucinations”. This makes AI a potential amplifier of misinformation for several intertwined reasons. One is the fluency bias, in that clarity is confused with truth. Another is that AI algorithms know so much from training with a staggeringly massive amount of data that it sometimes blend facts from multiple domains to come up with predictions that are a statistical fit, but completely falso.

AI may be an amalgam of the world’s best explainer and the world’s worst fact-checker.

In an information ecosystem driven by social media, virality and speed, clarity has become one of the most powerful tools. The ability to translate expertise into accessible truth has become an ethical responsibility. Alternative facts do not exist. Therefore, overcoming the curse of knowledge means recognizing that being right isn’t enough, because knowledge only matters if it is clearly and unambiguously understood.