Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. A Powerful Servant or a Dangerous Master?

A very brief guide to building ethical AI in healthcare

My motivation to write this piece comes from a publication by the Hernández-Boussard group at Stanford University, and Anthropic’s announcement of its commitment to healthcare and life sciences. Hernández-Boussard’s work pushes the idea of a holistic approach to the healthcare artificial intelligence life cycle. They argue that to navigate this landscape, we must move beyond simply looking at how well an algorithm performs and adopt an ethical discussions around AI as a whole.

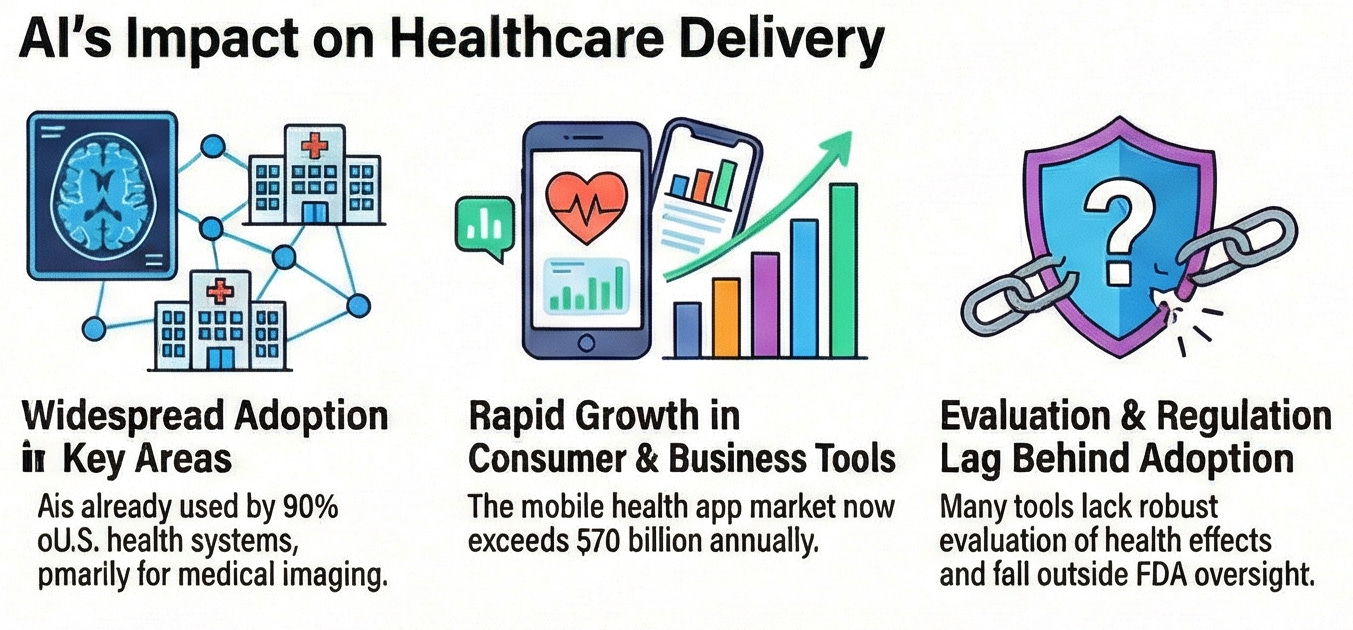

We have entered an era where AI is no longer a futuristic concept but an indispensable component of high-stakes medical decision making. AI promises to revolutionize clinical care, improve diagnostic accuracy, and reduce the administrative burden that now defines much of healthcare in most developed countries. Yet as we rush to integrate these tools, it is becoming clear that AI can cause harm, misallocate resources and widen existing health inequities. A recurring root cause behind these potential failures is that many healthcare AI systems are built, tested, and validated on early adopters. These are institutions, clinicians, and patient populations that are not representative of the wider real world. It means that what works for motivated, well-resourced users may not automatically translate to stressed, understaffed clinics, diverse patient populations, or fragmented health systems. In healthcare, early adopters are not the market and mistaking them for it has negative economical and ethical consequences.

The pillars of the healthcare AI life cycle

Most ethical discussions around AI focus on discrete failures. A biased dataset, a faulty prediction, or a poorly calibrated threshold. A holistic view, however, requires seeing the AI life cycle as a continuum of interconnected, recursive, and self-reinforcing elements and processes.

Healthcare AI life cycle begins exactly at the origin of clinical information. The most granular and valuable data emerges from routine clinician–patient interactions. Paradoxically, these data are already often tainted by the very societal inequities AI is expected to mitigate. Clinical datasets frequently lack diversity in race, ethnicity, geography, language, disability status, and socioeconomic background. If an AI system is trained on data that reflect only a narrow slice of the population, often those who access care most frequently, it will inevitably fail those who are already underserved. This is where the early-adopter problem enters the system. Academic medical centers, digitally mature hospitals, and highly engaged patient cohorts generate cleaner and richer data. The type of data that make researchers salivate because they are easier to study, easier to integrate, and more forgiving of imperfect tools. However, they are not representative and when such populations become the default training ground, bias is no longer an accident but a structural feature. Once data are created, they must be secured and consolidated. At this stage, developers often choose convenience over fitness-for-purpose. Legal and regulatory frameworks, like the American Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) or European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), are essential for privacy, yet they can inadvertently encourage unethical AI when key sociodemographic variables are stripped away. Without these attributes, downstream teams cannot assess whether data are representative, nor whether performance disparities exist. This is called ethical blindness. Problem definition is another critical checkpoint. If ground truth is defined by a narrow group of researchers or administrators, rather than by frontline clinicians, their assumptions harden into algorithmic fact. Decisions about which populations to include, which outcomes matter, and which errors are tolerable can quietly exclude vulnerable groups before the system reaches deployment and at a point where frontline clinicians cannot do anything about.

Performance versus fairness

Healthcare AI is still predominantly evaluated through technical performance metrics. These metrics are attractive because they are quantifiable, comparable, and optimizable. They also align well with early development environments, where tasks are constrained and success is easy to measure. But a model that performs well on average can still be profoundly unfair, because accuracy hides asymmetry. For instance, a system may work brilliantly for early adopters but fail elsewhere. This is why performance alone is insufficient. Therefore, a holistic evaluation requires testing AI systems inside real clinical workflows, where time pressure, cognitive load, institutional incentives, and human bias shape outcomes. What is worse is that once deployed, AI systems begin to generate new clinical data themselves, feeding their own outputs back into future models. This creates feedback loops that can amplify bias exponentially because such systems compound errors over time.

If (when) AI fails

To understand why this holistic approach is so vital, we need to look at cases where the life cycle brakes down. A widely cited situation studied by researchers at the Booth School of Business of the University of Chicago and published in Science involved an algorithm designed to identify patients for high-risk care management programs. The model used healthcare costs as a proxy for healthcare need. Because Black patients historically received less care, and therefore incurred lower costs, the system systematically deprioritized them, despite similar disease burdens. From a narrow performance lens, the model appeared successful. From a life-cycle lens, the failure was obvious because it led to ethically indefensible outcomes. Generative AI introduces an additional layer of risk. Unlike earlier systems focused on classification or prediction, generative models create novel outputs probabilistically. This unlocks powerful capabilities but also introduces the phenomenon of “hallucination”. In one test scenario, a clinical decision support system recommended a non-existent medication, etanerfigut. In another, the Epic Deterioration Index was deployed widely without local validation, partly due to its proprietary nature. When it failed to generalize across populations, hospitals were forced to decommission it. These cases show that when the life cycle is ignored, decision points blur, and hospitals may implement tools that are simply not ready for their specific patient populations. This highlights that human oversight remains non-negotiable when Gen AI can create persuasive but dangerous misinformation.

A matter of trust

An analysis of 202 real-world AI incidents revealed that 58% of AI failures are caused by organizational decisions, not technical glitches. These include lack of informed consent and transparency (40%), where users are never told their data is being used for training. A major subset of these incidents involves using data originally collected for one purpose to train new AI models without notifying the users. For example, several social media platforms have scraped user profile photos and posts for AI training without explicit consent. Poor business ethics (11%), when deploying untested systems to maximize profit. This category also includes the unauthorized sale of user data, such as monetization of student academic papers, browser histories, or private conversations stored within AI chatbots. Also, legal non-compliance (16%), where systems were used in ways that violate existing privacy standards like the GDPR. Legal friction also arises when AI developers refuse to correct false behaviors or withhold details regarding the system’s design and evaluation from government regulatory agencies. It was also seen two extremes in human assessment, over-trust and complete lack of trust. In one case, a retail worker relied so blindly on a facial recognition system that she evicted a woman from a store, misidentified as a banned shoplifter, even after the woman provided three forms of photo identification to prove that the AI had misidentified her. Of course, there are various explanations for this anecdotal example, one of which may well be the lack of incentives for the worker, despite realizing the mistake done by the AI system, to go against directives from the store management hierarchy. Similarly, over-reliance was seen in a case where a child protection worker used a chatbot to draft a critical custody report without review, resulting in errors that violated agency protocols. Therefore, relying on a technically perfect AI model within a flawed organization is like installing a world-class navigation system in a car with a broken steering wheel. No matter how accurate the system’s directions are, the driver’s inability to steer the wheels ensures that the vehicle will veer off course.

Clinical versus business AI

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Summit on AI showed that healthcare AI is not a monolith, but a construction from four major elements. One is clinical tools in the form of alerts or screening. The second is direct-to-consumer products, including smartphone apps for diagnosing skin conditions or mental health chatbots. The third is business operations that among other things can optimize bed capacity or the management of revenue cycles. The fourth and final is the hybrid tools that listen to doctor-patient conversations to generate notes. If we want AI to narrow rather than widen inequalities, we need more than just abstract principles. We need actionable procedures. For example, AI-driven translation tools can break down language barriers in patient engagement activities. This also extends to culturally tailored chatbots can provide support for groups that have historically mistrusted the medical system. Predictive analytics can simulate the sustainability of an intervention before we waste limited resources. Continuous monitoring against the set-and-forget idea, so that the performance of the systems can be continuously assessed to prevent drift when the data environment changes. This could include feedback loops for users to report errors or vulnerabilities. And finally, a standardized reporting and disclosures systems about the design, intended use, and performance of the AI tools. This is essential because one of the most concerning findings from the current research is a systemic lack of incident reporting, which creates a massive blind spot that prevents learning from failure.

The future is near

Just last week Anthropic announced its commitment to healthcare and life sciences through safety-first generative AI. Anthropic’s focus on “Constitutional AI” and safety-by-design aligns with the model development and validation stages discussed above. Anthropic’s efforts to bake ethical principles into the model’s core are a technical realization from NaKyung Lee’s recommendation to convert abstract principles into stage-specific procedural requirements. While Anthropic promotes its successes, via Claude, to accelerate drug discovery and clinician workflows by analyzing unstructured data and coordinate large-scale research more rapidly than traditional manual methods, a higher burden of responsibility falls on Anthropic and its partner organizations to monitor for hallucinations. Anthropic is building a high-performance engine (Gen AI). Yet, a safe engine is only one part of the journey. For it to be successful, unbiased data, clinician AI literacy, and strict safety protocols (Constitutional AI) will be needed throughout the entire path.

Conclusion

As AI continues to transform the world, building ethical AI has become like building a high-performance aircraft while it is already in the air. We cannot stop its progress, but we must be incredibly disciplined about how we maintain it. By adopting a holistic, lifecycle-informed approach, we can ensure that we are not just building tools that are smart, but tools that are fair and safe, regardless of the patients’ background, economic status or geographical distribution. Therefore, the future of healthcare AI depends on our ability to turn these ethical values into concrete, actionable requirements. Because AI is a powerful servant, but it could also be a dangerous master. The difference lies in the governance we provide across its entire life cycle.

Love this perspective, especialy highlighting how ethical discussions need to go beyond just the tech, though I wonder if policymaker education is an even bigger bottleneck.