The Non-Existing Dopamine Addiction

Science explainers on the internet argue that modern life is destroying productivity by making us addicted to dopamine. Yet, at present there is zero scientific evidence supporting such thing.

Lately, dopamine has gone from just another brain chemical mostly discussed in neuroscience labs to a celebrity molecule blamed for everything from smartphone addiction to our inability to complete work on time. A steady stream of best-selling books, podcasts, YouTube and TikTok videos have linked dopamine to digital-age malaise. However, a deep dive into the scientific literature yields zero credible evidence that dopamine addiction actually exists. Quite the opposite. Let’s explore this in detail.

Dopamine

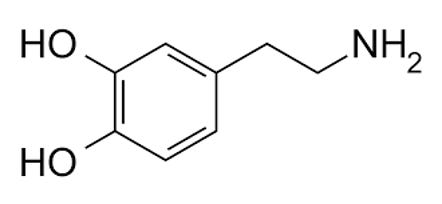

First, what is dopamine? Dopamine is a neuromodulator. That is, a molecule that neurons use to modify how they communicate with each other. It is essential for many of the brain’s most important functions, including movement, motivation, learning, reward and decision-making. Dopamine is mainly produced in a few small regions of the brain, namely, the substantia nigra, the ventral tegmental area and the hypothalamus.

Dopamine is not the pleasure chemical

Contrary to popular belief driven by pseudo-scientific explanations, dopamine is not a pleasure molecule. Experimental research over the last 30 years has shown that dopamine should be more accurately described as a signal of salience, motivation and reward (#here and #here). In other words, by itself it does not generate subjective pleasure. For example, studies in mice in which dopamine has been eliminated show that the animals can still show normal facial reactions to sweet tastes, indicating that they enjoy the food, but contrary to normal subjects, they do not work to obtain it. In other words, they do like the good stuff, but do not necessarily want it (#here). This distinction between wanting and liking is important because it is central to modern theories of reward.

Dopamine predicts value

The human brain uses dopamine constantly regardless of feeling. For instance, when moving, learning, deciding, and remembering things. Also, we use a lot of other essential chemicals for similar everyday activities, including oxygen and water. In other words, by definition, no one can be addicted to dopamine any more than they can be addicted to oxygen. In short, dopamine is not merely a bulb that lights up when something feels good. Dopamine motivates us to make an effort to achieve something that we know will feel good. Dr. Andrew Huberman from Stanford University has dedicated an entire video podcast to this topic (#here).

What is an addiction?

Maladaptive responses originally develop to cope with stress, threat, or emotion, but end up causing more harm than good in the long term. Skipping tasks that cause anxiety, aggression instead of communication, and self-handicapping are maladaptive behaviors. Addictions are also maladaptive. Addictions are relapsing disorders characterized by the compulsive seeking and use of a substance or engagement in a behavior despite knowing its harmful consequences. Addictions are not simply about pleasure or weak will, but a complex interaction between genetics, psychology and the environment. Biologically, addiction involves alterations in brain circuits related to reward, motivation, learning, and self-control, particularly within the mesolimbic dopamine system. Repeated exposure to drugs or highly reinforcing behaviors can produce neuroadaptations that increase cue sensitivity and craving, while reducing the ability to derive pleasure from everyday activities. Psychologically, addiction often coexists with poor emotional regulation, leading individuals to use substances as coping strategies. Social and environmental factors, including availability, peer influence and socio-economic stress, strongly shape vulnerability to addictions. Therefore, addiction are best understood as a brain-based disorders of learning and motivation. Ultimately, addiction is a relentless pursuit of reward or relief, even when it destroys the very things that make life rewarding.

Dopamine and addiction

The neuroscience literature agrees that addictive drugs increase dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway, particularly in the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens. Also, dopamine is a phenethylamine, and many controlled substances are structurally derived from this molecular backbone. Examples of phenethylamines include many drugs that generate dependency, like amphetamine, methamphetamine, and MDMA (Ecstasy). Medications that activate dopamine receptors include Ropinirole. Others, like cocaine, do not resemble dopamine, but functionally mimic or amplify dopamine activity in neuronal synapses. Usually, the effects of these drugs arise because they increase dopamine release, block re-uptake (the normal mechanism by which the body controls how long a nerve signal lasts), or act as activators (agonists) of dopamine receptors. Although repeated exposure to controlled substances drives neuroadaptations that include dopamine, in addiction, people are not chasing dopamine itself. They are chasing drug-induced states and learned associations. Dopamine is the mechanism, not the target. The general scientific consensus is that addiction emerges from maladaptive neuroplasticity in reward circuits, habit learning, stress systems, and executive control, not from a surplus of dopamine. Therefore, saying “dopamine addiction” is like calling over-eating “insulin addiction.” The insulin system is involved, but insulin itself it is not the object of desire.

Procrastination

One of the most persistent claims in this genre is that we are addicted to dopamine, and that this addiction is the fundamental cause of procrastination. Procrastination is the voluntary delay of an intended task, despite knowing that postponing it will likely lead to negative outcomes. People procrastinate not because they don’t care, but often because the task triggers unpleasant emotions such as anxiety, doubt or fear of failure. By postponing, they get short-term relief (#here).

Over time, avoiding discomfort becomes habitual, reinforcing procrastination. This helps explain why procrastination persists even in people who logically know what they should do, care about outcomes, and are capable of the required effort. The above sounds familiar to dopamine activity, right? Therefore, some people concocted the idea that if only we could detox or starve the brain of dopamine, we would finally become disciplined, focused, and productive. This is, plain and simple, untrue as it is not supported by any direct evidence. In addition, if we were to eliminate dopamine, we will simultaneously generate apathy, low motivation, and reduce goal-directed actions. And the claim goes “we procrastinate because we are addicted to dopamine spikes from social media, video games, and instant gratification”. The problems with this argument is that there is no scientific evidence that everyday procrastination is caused by altered dopamine systems. No one has ever shown that people that procrastinate have abnormal dopamine levels, dopamine release, or receptor density. Manipulating dopamine activity, for instance in Parkinson’s patients receiving activators of the dopamine system, has not been shown to change behavior towards completing tasks. No study has shown that dopamine makes people start tasks sooner, or reduce delay. Procrastination is an emotion-driven avoidance behavior. It is less “I want reward now” than “I want to avoid discomfort now.”

Social media

While social media can be habit-forming, endogenous dopamine release from engaging in them is minuscule compared to drugs of addiction. For example, cocaine can increase dopamine by 1,000%, whereas message notifications may increase dopamine by less than 10%. Then, why the narrative took over? The “dopamine addiction causes procrastination” narrative became attractive because it puts the blame on a concrete biological system that sounds sophisticated, and whose main character, dopamine, has been linked to pleasure. Its suffix (word ending), “amine”, immediately suggests “illegal drugs”. Also, the narrative provides a villain (technology) and, importantly, it offers simple solutions (detox). But from a scientific perspective, it is wrong and extremely reductive because humans procrastinated long before smartphones and even the internet. According to lore, Leonardo da Vinci, a brilliant and curious artist and engineer, was perhaps the most famous procrastinator in history. He started, and abandoned, countless projects and apparently took 16 years to complete the Mona Lisa (#here). The Roman poet Ovid wrote “I see the better course and approve it, but I follow the worse.” (#here). This is procrastination 2,000 years before TikTok.

Dopamine detox is a simple cultural phenomenon masquerading as neuroscience

The recent fad of “dopamine detoxing” of “dopamine fasting” claims that abstaining from stimulation resets the reward system. However, there are two problems with this rationale. First, dopamine, using widely accepted definitions, should not be considered a toxin. There are modifications of dopamine (oxidation) that could become toxic to brain cell (#here), but this is not the dopamine form that people claim you need to “detox” from. Second, the brain never runs out of dopamine because you watched a lot of TikTok. This is because the dopamine system is highly resilient and will always go back to a baseline. Experiments have shown that if you deprive animals of stimulation, dopamine production does not vanish. Actually, it often increases to maintain an equilibrium. Therefore, no one can meaningfully reset dopamine levels with a weekend retreat in the woods and with no access to internet. As Dr. Peter Grinspoon, editorial advisory board member at Harvard Health Publishing eloquently put it “You can’t fast from a naturally occurring brain chemical“ (#here). In conclusion, dopamine is deeply involved in addiction, but people do not get addicted to dopamine itself.

What can we do?

Indulging in social media may be a way to occupy time while we postpone completing a task, but it does not cause procrastination. If there was no YouTube or Instagram, procrastinators will find other things to do instead of doing what must be done. Dopamine does not cause procrastination. Smartphone-induced reward hijacking does not cause procrastination. Blaming dopamine or technology for procrastination obscures the psychological and biological reality that no one is addicted to dopamine. Dopamine addiction is a compelling narrative, simple, dramatic, relatable and actionable. But it is wrong. Finally, we do not procrastinate because tasks are insufficiently stimulating. We procrastinate because tasks threaten us emotionally (#here). Understanding and changing your relationship with discomfort is hard. It requires self-awareness, practice and vulnerability. No wonder “dopamine detox” sells better. But in the end, the solution to procrastination is not less dopamine or less TikTok. It is to learn how to face discomfort and get stuff done.